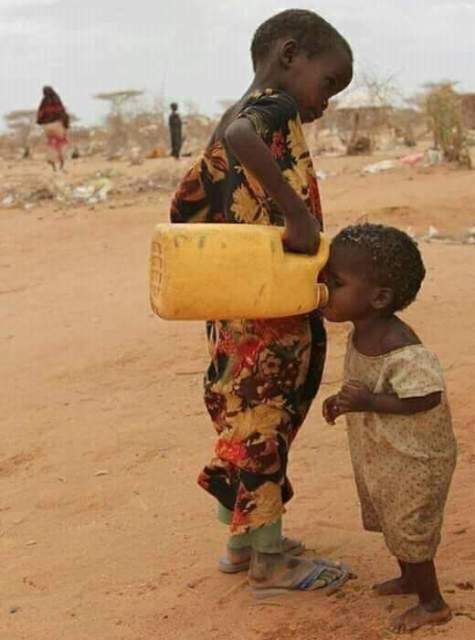

Over the last 30 years in Somalia, recurrent droughts and floods have become more intense, frequent and unpredictable, linked to climate change. In October, Somalia has been devastated by floods, affecting over half a million – or 574,000 – people. Hundreds of thousands of them have been forced to leave their homes and many of them are in dire need of clean water, shelter, health and food supplies.

Earlier in the year, the January to March Jilaal season was abnormally hot and dry, and the Gu’ rains, which usually come between April and June, arrived late and then in overabundance across most of the country. This caused massive crop failure and wiped out many herders’ livestock, threatening millions with starvation. Early aid efforts fended off the worst of a hunger crisis, but families are near to breaking point as they now face yet another extreme weather shock.

On 21st November 2019, young boys wade through flood water in Bardheere, Somalia. Credit: UNICEF

Ruun Mohamed Ahmed, 35, was at home when water started flooding streets in her neighbourhood of Koshin in Belet Weyne town, Hiraan region, Somalia. Even then, she was not sure what to do, until the water reached her home and swamped her house.

“It became dangerous, the water was about to wash away both my home and my children,” she said. “We had to leave quickly and could not take even the basics. We did not think we would be away for long, but it is now two weeks.”

Ruun and her family of 10 now live in a makeshift shelter on higher ground in Caale Jaale village, 5 kilometers away. Ruun washes clothes for other displaced people to support her family. She is the sole bread winner after her husband died two years ago.

Ruun and her 10 children were displaced from Belet Weyne and she is now washing clothes to survive. Credit: UNOCHA

A mother rebuilds her makeshift shelter following heavy rains and flash flooding in November. Credit: Nasser Arush/ SWS

Flooding inBaidoa town , following heavy rains in November 2019. Credit: UNOCHA

Hundreds of thousands displaced

Ruun is among 370,000 people who have been displaced by the floods. As the rains intensified, water levels in the Shabelle and Juba rivers rose, breaking their banks, flooding vast areas. These floods are unusual for this time of year and as such, they strike at a time when there is less funding and flexibility in the humanitarian operation.

Many of the affected communities are the same ones that suffered severely during the 2016-17 drought crisis, which brought the country to the brink of famine just two years ago. With little time to recover between shocks, communities are highly fragile and coping mechanisms have been eroded.

Prior to flooding: drought and crop failure

Prior to the flooding, much of the country experienced drought conditions, which the poor Gu’ rains when they finally arrived, could not assuage. As a result, harvest yields were up to 70 per cent below average, mainly in the south – the lowest yield since record keeping began in 1995.

A dried-up water catchment in Odweine District, Somaliland in April 2019. Credit: WFP

People displaced by drought in a temporary settlement in Abudwaq, May 2019. Credit: WFP

Aerial view of flooded Belet Weyne town. Credit: UNOCHA

“A race against time”

Humanitarian partners are racing to deliver desperately needed assistance, flying several helicopter and plane rotations daily, loaded with supplies. OCHA is helping to ensure the deliveries are closely coordinated between partners and the local authorities. Many humanitarian agencies are re-directing their assistance to flood-affected communities, but there are not enough resources to cover everything. As a result, they have launched a flood response plan to raise $72.5 million for a three month swift response. Some $18 million has been provided from the UN’s emergency fund, the CERF and the Somalia Humanitarian Fund.

Despite the scale-up of assistance, significant gaps remain, particularly when it comes to emergency shelter and water, basic cooking equipment and solar lamps, safe drinking water and sanitation supplies, nutrition support for infants, medicines and health supplies, and services to protect women and children.

“We need a permanent solution,” Shashamey said. “Life cannot continue like this.” Aid workers agree that urgent action is needed to mitigate the increasingly negative impact of climate change in Somalia.

“It is a race against time,” said Justin Brady, head of OCHA in Somalia. “But while we must work with authorities to meet today’s needs, it is urgent that we also focus on long-term, durable solutions. Given the increasing impact climate change is having on Somalia, the challenges are only likely to become more frequent and more severe.”

Situation in Belet Weyne

Belet Weyne district is the worst affected with 231,000 people displaced and Belet Weyne town virtually submerged under flood waters.

The floods have also extensively damaged farms, property and infrastructure. “I owned a donkey cart before the disaster, but the donkey got lost when I was evacuating my family,” said Shashamey, a man displaced by floods. “I want the water to recede so that I go back home.”

Extreme weather events, driven by climate change, have increased in frequency and intensity in Somalia, worsening humanitarian needs in an already fragile country. Somalia has also faced years of armed conflict and instability, amid widespread poverty.

“I am worried about going back to Belet Weyne, my home is completely washed away,” Ruun said. “Going back means starting everything a fresh. Life will not be easy in coming weeks.”